If you search online for methods of calculating π, you’ll find countless ways. This is yet another one, probably complex, definitely imperfect, but at least you’ll learn more about the Monte Carlo methods.

The value of π

I’m pretty sure you’ve met π before. It should have been part of your school years, but I don’t expect you to have fond memories of it. It has been part of plenty of works of science fiction too, where one of my favorites is Carl Sagan’s Contact.

π is an endless sequence of digits, starting with 3.1415926535897932384626433832795. For those of us old enough to know what a slide rule is, it was right there, waiting to be used in calculations. In geometry, if you needed to straighten a circumference, you’d multiply the diameter by 22 and divide by 7; 22÷7 is 3.142… (far from π, but close enough given the limited resources). When electronic calculators became popular, one could use 355÷113 (3.14159292…; closer, but not yet perfect).

In theory, one should be able to determine π precisely through a simple division. If the length of a circumference is π times the diameter, then you could simply measure the circumference and the diameter, and then divide the former by the latter. Possibly a more precise calculation would be to divide the area of a circle by the square of the radius. Unfortunately, both methods fail because the precision of the result is limited to the precision of the measurements.

Or you could use a statistical method, couldn’t you?

Monte Carlo experiments

Monte Carlo methods (or experiments) are a set of algorithms that rely on repeated random sampling to obtain numerical results.1 In practical terms, you collect so many random numbers to see which ones conform to the rules you’re evaluating. If you’re still scratching your head, let’s jump to action!

Area of a circle: π×r²

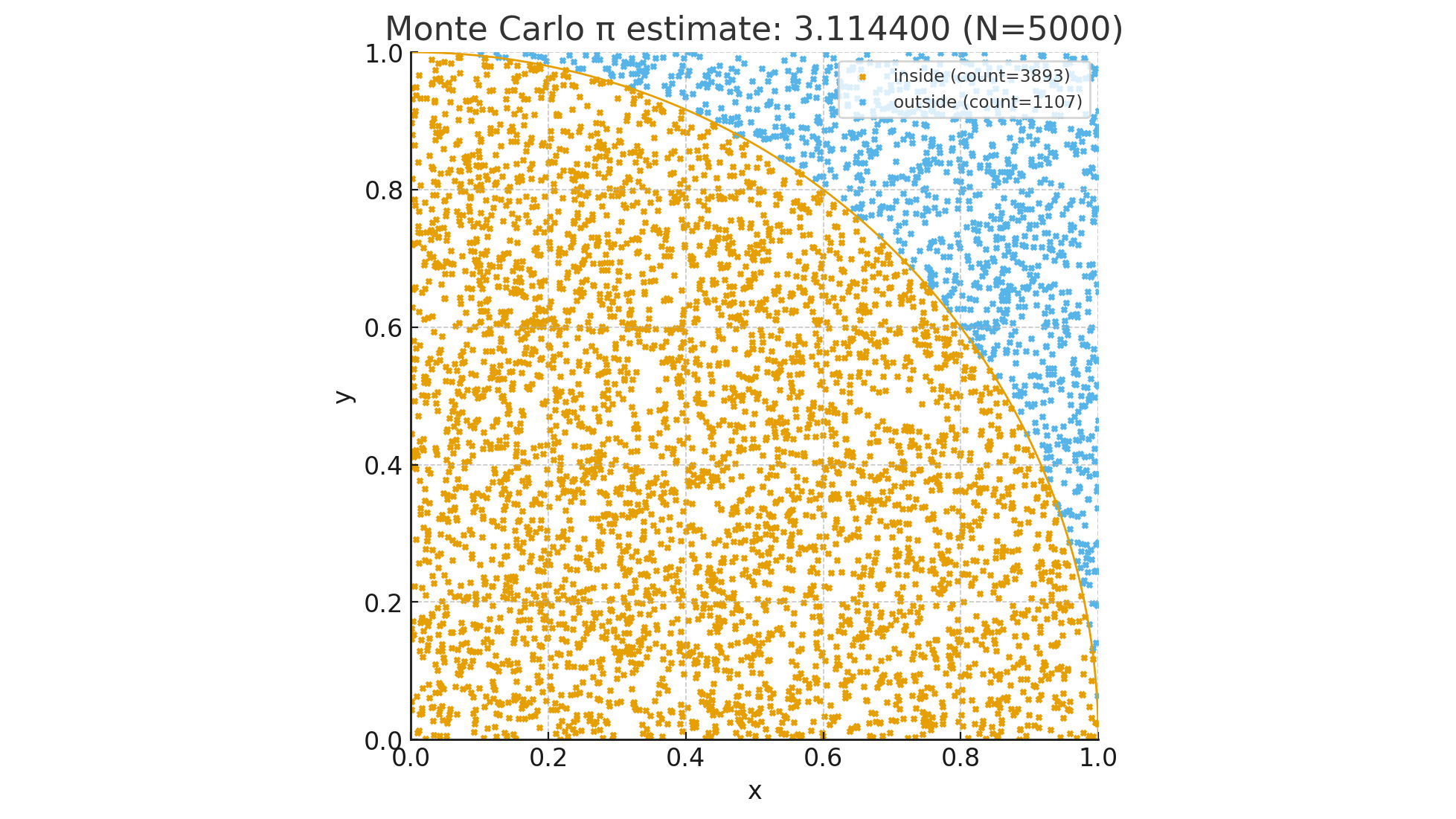

As mentioned earlier, you could determine π by dividing the area of a circle by the square of the radius. Assuming you have a circle inscribed in a square, that is, a circle enclosed in a square and intersecting all four sides, then you could start selecting random points inside the square and choose the ones inside the circle. If you then divide the number of points inside the circle by the total number of points, you’ll have a good approximation. Also, the more points you use, the more precise the result.

Let’s create a computer program for this simulation. To make matters easier, let’s set the radius to 1 (one squared is still one). To make it even easier, let’s use a quarter circle inside a quarter square, just like the picture at the top of this page. For this program to work, we’ll make it choose X and Y coordinates between 0 and 1 for each point. If the distance between the center of the circle and the point is 1 or less, then it’s inside the circle and outside otherwise.

Here’s the Python program:

import secrets, sys

get_random = lambda: secrets.randbelow(1000) / 1000

is_inside = lambda x, y: x*x + y*y <= 1

n = 100_000_000 if len(sys.argv) == 1 else int(sys.argv[1])

inside = 0

for i in range(n):

if (is_inside(get_random(), get_random())):

inside += 1

print(inside * 4 / n)

We’re using secrets because it uses the computer random number generator, and we accept a command line argument with the number of points to use (default: 100 million). Because we’re using a quarter of a circle, we need to multiply the result by 4. A sample run on my computer gave me 3.14564084 but it took longer than a minute and a half; I can’t wait that long! For the record, it’s a 13th generation Intel i9 with 20 cores at 5.4GHz; it’s a very powerful machine, but certainly not enough for this exercise.

Or is Python the problem? Python is incredibly powerful and easy to use, but for heavy calculations, it’s not necessarily the best choice. Let’s rewrite the program in Go:

package main

import (

"fmt"

"math/rand"

"os"

"strconv"

)

func main() {

inside := 0

n := 100000000

if len(os.Args) > 1 {

n, _ = strconv.Atoi(os.Args[1])

}

for range n {

x := rand.Float64()

y := rand.Float64()

if x*x+y*y <= 1 {

inside++

}

}

fmt.Println(float64(inside) * 4 / float64(n))

}

How does it perform? On the same computer, it gave me 3.1415122 in less than a second and a half, and 3.1416738 on the second run. Depending on the version of Go you have, you could replace math/rand with math/rand/v2, which will cut your execution time even further; for example, it gave me 3.1416448 in a little over 1 second. If I wanted to use more points, therefore increasing the precision, I could use 1 billion points for example; one result was 3.141558076 and it took almost 11 seconds.

I don’t love this outcome…!

I really don’t. That was too much effort that didn’t bring me much closer to π than 22÷7. Going forward, if I want to use π, I could use math.pi on my Python programs or, if I really wanted precision, I could head over to ClickCalculators.com and get 1,000 digits.

At the least, I brought you the Monte Carlo experiments, which you might find valuable.

And it made me curious too: how would other programming languages perform?

Other languages and tools

Spoiler alert: the table at the end of this article shows how each alternative performed.

More Python

Random number generation is a complicated matter. It involves a series of calculations based on an initial value, usually referred to as “seed.” Because random numbers can be used in cryptography, if one could replicate the seed than all cryptography is dismantled. In my initial program I was using secrets because it relies on the operating system itself, which makes it more secure. The tradeoff is that secrets uses /dev/random, which is a special file, and reading from files incurs delays. Let’s rewrite the program to use random instead.

import random, sys

def calculate(n: int) -> float:

inside = 0

for i in range(n):

x = random.random()

y = random.random()

if x*x + y*y <= 1.0:

inside += 1

return inside * 4 / n

if __name__ == '__main__':

n = 100_000_000 if len(sys.argv) == 1 else int(sys.argv[1])

print(calculate(n))

I also made the calculation into a function. The reason will become clear soon. Meanwhile, it must be noted that, instead of a minute and a half, it took slightly over 9 seconds.

One characteristic of Python is that each program runs on a single CPU core. No matter how many cores you have, the program will only use one. For enterprise applications, this makes it beneficial because it’s easy to scale, but for calculation-intensive applications you’re not leveraging the full power of your computer. There are tools and mechanisms to spread your program execution across multiple cores, but it usually involves a major rewrite of your program.

Another characteristic of Python is that the program is compiled at runtime. Depending on the case, this incurs slower execution time and increased resource usage. Specifically for numeric calculations, Numba could be your friend. Its first trick is to pre-compile the code so it doesn’t have to be interpreted at runtime. All it takes is a single @njit decorator and obviously importing the Numba library.

import random, sys

from numba import njit

@njit

def calculate(n: int) -> float:

inside = 0

for i in range(n):

x = random.random()

y = random.random()

if x*x + y*y <= 1.0:

inside += 1

return inside * 4 / n

if __name__ == '__main__':

n = 100_000_000 if len(sys.argv) == 1 else int(sys.argv[1])

print(calculate(n))

Impressively enough, it ran in less than 2 seconds (almost 5 times faster).

Another benefit is that Numba can spread NumPy array expressions across multiple CPU cores, which could speed it up. It’s all a matter of adding @njit(parallel=True).

Mojo

Mojo is a relatively new language. For example, I’m currently using version 0.25.6.0, which is the latest on Arch Linux. The standard library is open source, but the compiler not yet. Its syntax is similar to Python and programs can be compiled to run on any hardware, including GPUs. The program, as expected, is rather straightforward:

import random

from sys import argv

def main():

n = 100_000_000 if len(argv()) == 1 else Int(argv()[1])

random.seed()

inside = 0

for _i in range(n):

x = random.random_float64()

y = random.random_float64()

if x*x + y*y <= 1:

inside += 1

print(inside * 4 / n)

How did it perform? Not as well: longer than 12 seconds. If I had a GPU I could report better numbers, but I don’t have one, ergo I can’t. Perhaps you can?

Comparison

In alphabetical order, this is how the different languages and tools performed. I’m omitting the calculated value of π because, for this exercise, it has become irrelevant.

| Name | Iterations | Sample Duration (seconds) |

|---|---|---|

| Go | 100M | 1.119 |

| Mojo | 100M | 12.827 |

| Python with Numba | 100M | 1.902 |

Python with random |

100M | 9.265 |

Python with secrets |

100M | 100.849 |

Revision history

- 2025-09-27: Original posting date.

- 2025-10-08: Speeding up Python; Mojo.

References

-

Source: Wikipedia: Monte Carlo method ↩